The Valley of the Kings

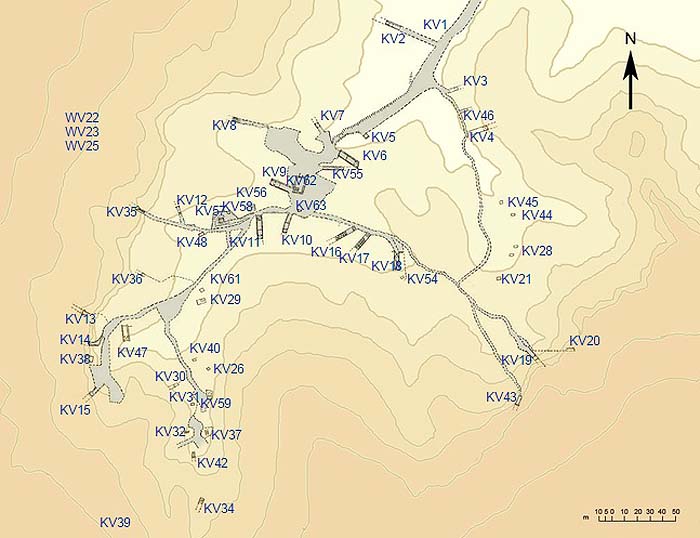

On the west bank of the Nile lies the Valley of the Kings, a necropolis used to house the bodies and belonging of many pharaohs from Thutmose I all the way until Ramesses X or XI. There are 63 tombs in the area, built there between 1539 BC to around 1075 BC.

The Valley of the Kings is one of the earliest examples of a necropolis, (literally, a ‘city of the dead’). A veritable burial ground of the great pharaohs and noblemen of Egypt for a period of time that spans 500 years, the Valley of the Kings remains one of the richest sources of Ancient Egyptian history.

Properly referred to by scholars as ‘The Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in the West of Thebes’, or ‘The Great Field’ (Ta-sekhet-ma’at in ancient Egyptian and Coptic), it is also referred to as the Wadi al Muluk, or the Wadi Abwab al Muluk in Egyptian Arabic.

© Hannah Pethen - The Valley of the Kings

Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979, it remains a popular tourist destination spot for both foreigners and locals. Although its primary importance comes from being among the most well-known, integral hub for a majority of today’s archaeological and Egyptological endeavors.

Where is the Valley of the Kings?

The Valley of the Kings is located on the Western bank of the Nile River, opposite modern-day Luxor, and was previously known as Thebes. The Valley of the Kings is a necropolis within a necropolis, being situated at the heart of the Theban Necropolis itself, and consists of two valleys – the Eastern and Western Valleys, the whole of which being dominated by the peak of al-Qurn.

Known to the Ancient Egyptians as ‘the Peak’ (ta dehent), al-Qurn later became the theoretical inspiration for the Egyptian Pyramids. Being deep in the heart of an arid, barren stretch of desert land, this was an ideal burial ground for ancient Egypt’s royalty, nobility, and all other social elite families that could afford a tomb, thanks in part due to its secluded nature.

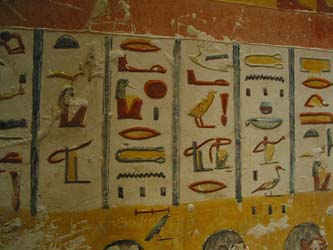

© globetrotter_rodrigo - Tomb Wall Hieroglyphs

Climate

The inhospitable climate of the area around the valley – blistering hot days, and freezing cold evenings, made it unsuitable for people to live and thrive. This prevented, in some measure, grave robbery which was common for the time. However, the harsh climate did little to deter the truly daring thieves to rob tombs that were in any way accessible.

On the other hand, the unforgiving temperatures of the Valley of the Kings helped the later practice of mummification in becoming more successful, especially since the practice of embalming became the crux upon which the whole of Ancient Egypt’s spirituality stood.

© Troels Myrup - Path into the Valley

Geological and Topographical Layout of the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings is located in an area that consists of mixed-soil conditions. The necropolis is actually in a place called a wadi, which is composed of various concentrations of hard, nearly impregnable limestone and softer layers of marl.

The Valley is known not only for the enduring quality of its limestone, but for its network of natural caves and tunnels, as well as the natural ‘shelves’ which descend below a scree that leads to a bedrock floor.

These networks of natural caves existed prior the development of Egyptian architecture, although the discovery of the shelving came about recently, thanks to the effort of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project, which helped to shed some light on the complexity of the Valley’s natural structures sometime between 1998 and 2002.

© Elena Pleskevich - Cliffs in the Valley

History of the Valley of the Kings

The earliest tombs located in the Valley of the Kings were opportunistically placed in naturally formed clefts, well-hidden in the crags of limestone bluffs or cliffs.

In these clefts, the softer marl and worn or eroded limestone could easily be chipped off to create entryways for the bodies of the departed. Later, deeper chambers were built, or natural tunnels and caverns were used as de facto crypts for royalty and the nobility.

After 1500 B.C., the Egyptian kings no longer undertook great projects like building pyramids, while The Valley of the Kings become the main designated burial location.

The practice of constructing elaborate tombs predates the Valley as the established graveyard of Pharaohs by several hundred years. It is believed to have begun right after the defeat of the Hyksos and the rise of Amenhotep’s father, Ahmose I (1539–1514 BC).

© Hannah Pethen - Paths Leading to the Tombs in the Valley

For a period of over five hundred years (1539 to 1075 BC), the Valley of the Kings was a place used for entombment of Egyptian royalty, although the very name of the valley itself is somewhat misleading. In fact, there was in no true sense an ‘exclusivity’ in the burials allowed within the necropolis.

It is now known that many of the tombs were not used for kings. Instead, some belonged to influential people such as members of the royal household, wives, trusted advisers, nobles, and even some commoners.

It was not until the Eighteenth Dynasty that some measure of exclusivity was implemented for interment in the Valley, so much so that a ‘Royal Necropolis’ was especially created chiefly for the purpose. This gave rise to the highly complex and ornate tombs that have become a trademark of pharaonic crypts, although the occasional common burial for court servants and their ilk were relegated to mere rock-cut tombs or niches.

© Joanne and Matt - View of the Necropolis

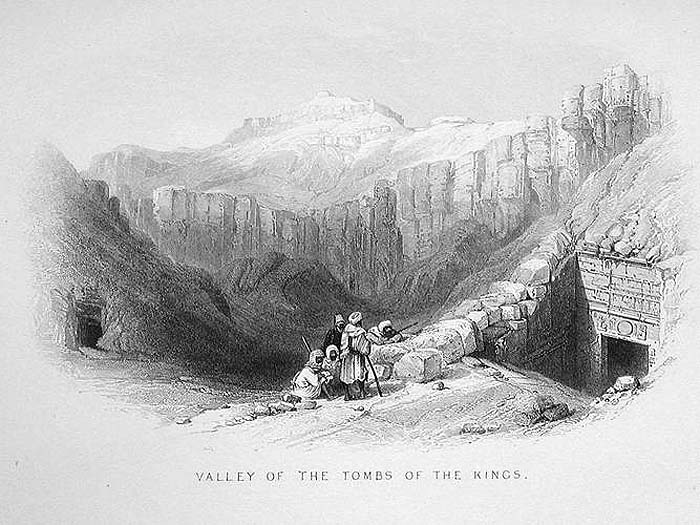

Discovery and Exploration

The discovery of ancient tombs in the Valley of the Kings is nothing new. In fact, prior to the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, an already staggering number of 62 prominent tombs had already been explored. Many of these were small tombs, which were basically single holes in the ground, while the very large ones revealed over 100 other underground chambers.

Unfortunately for modern archaeological explorers, most of these chambers and tombs were found to be looted by ancient grave robbers. Thankfully, the real treasure found there was the artwork of ancient Egyptians; these wall paintings allowed experts a glimpse into the lives of the Pharaohs and other significant people buried there.

© Exploring the Valley of the Kings, 1862

There is still excavation activity today, within the Amarna Royal Tombs Project (ARTP), which is an archaeological expedition that was established in the late 1990s. Some of the first tomb discoveries were many decades ago, using rudimentary tools, and these sites were not thoroughly excavated.

The on-going excavation works are making use of state-of-the-art technologies to in search for new information at older tomb sites, as well as at locations within The Valley of The Kings that have not yet been explored.

Architecture and Layout

Without a doubt, the ancient Egyptian architects were far more advanced than anyone could have imagined. Using the natural caverns within the valley, ancient architects carved walls, chambers and intricate pathways without any modern tools with surprising precision. Egyptians tools such as picks, hammers, shovels and chisels were made of wood, stone, ivory, bone and copper.

Although impressive, the architecture and layout of the Valley’s earliest burial tombs are inconsistent.

There are no unified patterns of the tombs’ layouts. Because of the unpredictability of limestone formations in the area, pharaohs invariably tried to choose what they perceived to be the more ‘superior’ spot, compared to their predecessors.

Later, the construction of large tombs became more ‘standardized’, with three corridors being followed by an antechamber and a ‘secure’, sometimes hidden, sunken sarcophagus chamber nestled in a very deep part of the tomb.

© Joonas Plaan - Tomb of Twosret in the Valley of the Kings

This was not ‘the’ standard design or layout of the axis of burial tombs for the Pharaohs. However, since some builders deviated from this unwritten rule, usually at the behest of the pharaoh who commissioned the tomb, sometimes more ‘fail-safes’ against robbery were added into tomb layouts.

Tombs in the Valley of the Kings

Which ones of the pharaohs were interred first in the Valley of the Kings remains debated to this day, it is assumed by many scholars that it was either Amenhotep I, or Thutmose I. While the veracity of the former is still uncertain, extant historical records dating back to the period prove that it was Thutmose I, who was one of the first pharaohs interred in the Valley.

The East Valley holds a significantly larger number of tombs than the West, which has only four known tombs. The tombs are known by the order of discovery: the first tomb found was Ramses VII and was given the label of KV1, where KV stands for "Kings' Valley". Not all of the tombs were used to house bodies, some only held supplies, while others were completely empty.

Source: Wikipedia - Tombs in the Valley of the Kings

Tutankhamun

In the East Valley, in 1922, Howard Carter found what was labeled KV62: the tomb of Tutankhamun.

While many of the tombs and chambers in the area were sacked by thieves, this one was intact and stocked full with treasures. Valuable things as jewelry, statues, weapons and the Pharaoh’s chariot, were valuable finds, but the real treasure was the magnificently decorated sarcophagus, with the young king’s remains inside.

© Kačka a Ondra - Inner coffin of Tutankhamun

KV62 was the last large find until early 2006, when KV63 was excavated; KV64 was later found using radar technology. These recent discoveries are as fascinating as the ones found earlier in the 20th century, though KV64 has yet to be excavated itself.

New finds in the Valley of the Kings shows that KV63 is not a tomb, but a storage chamber, as none of the seven coffins hold mummies; instead, there are clay pots used in the mummification process. However, the information has not yet been verified by the Supreme Council of Antiquities, as the find was not properly presented before the Council before sending out news of the find.

Ramses II

Unlike Tutankhamun, who died in his teens, another king survived much longer. Pharaoh Ramses II lived a full life and was also buried here.

Considered the greatest of all Egypt’s kings, his intention was to leave a legacy that would last forever. Grand statues of the Pharaoh were erected around Egypt’s great building projects like the Abu Simbel temples, for the purpose of distinguishing himself from other Pharaohs. As such, the tomb of Ramses II is nothing less than grand.

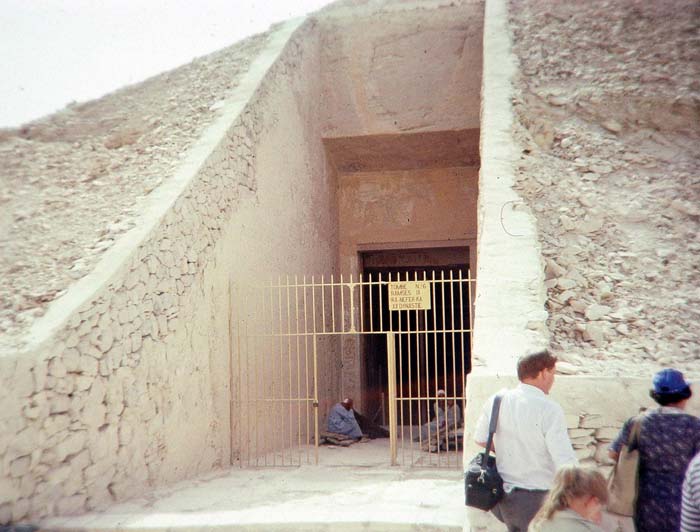

© Jimmy Smith - Entrance to the Tomb of Ramses II

It is one of the largest tombs in the Valley of the Kings, with a deep sloping entrance corridor, which leads to a grand pillared chamber. The corridors then break off into the well decorated burial chamber, and multiple side chambers. All of which are amazing feats of ancient engineering found in other larger tombs.

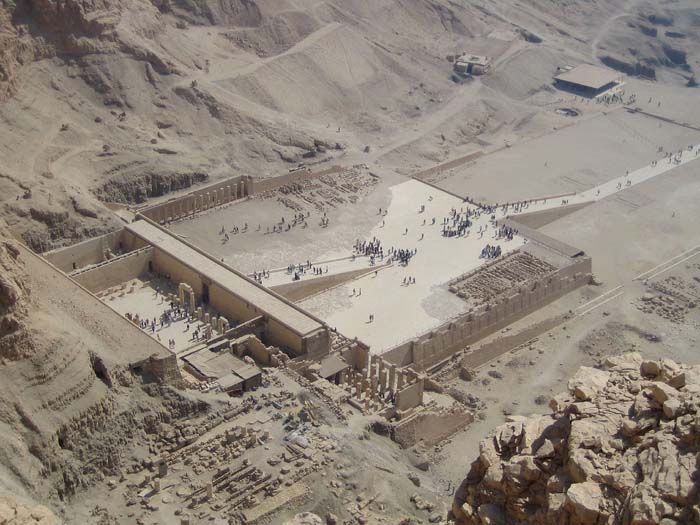

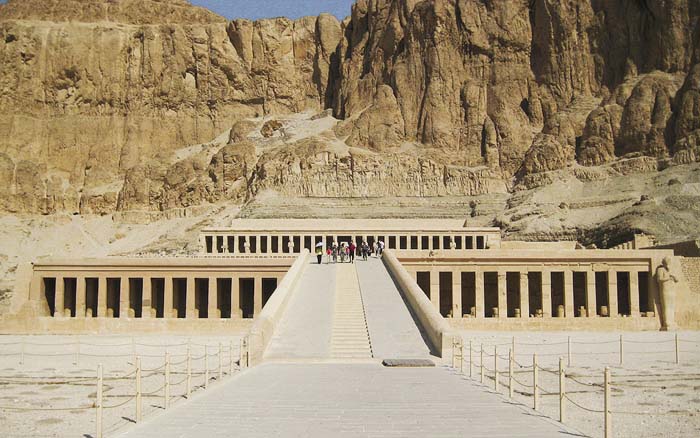

Hatshepsut's Mortuary Temple

In the nearby area of Deir el-Bahri is a mortuary temple commissioned to be built by Hatshepsut, the first woman to take the title King of Upper and Lower Egypt, as no title existed for the female equivalent; the closest there came was Queen Consort, and this was not her role at all.

The mortuary temple was found by a local family to house a large number of mummies; the family would remove artifacts from a mummy or two and sell them, though this came to a halt in 1881 when authorities found out and were sent to investigate.

© Mohd Tarmizi - Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

The mummies of over 50 kings, queens, and assorted nobles were moved from the Valley of the Kings to this temple by priests during the 21st Dynasty to preserve them from looting and desecration by grave robbers. Nearby, another cache was found holding the mummies of the priests that had moved the pharaohs to begin with.

Facts about the Valley of the Kings

- The Valley of the Kings was protected, for a time, by an elite order of guards called the medjay. They stood watch over the tombs, to make sure that grave robbers and commoners did not desecrate or attempt to inter their own dead in the Valley.

- The curse of the pharaohs is nothing new, these were a commonplace ‘safeguard’ employed by Ancient Egyptians, in an attempt to strike fear into superstitious and highly religious commoners who entertained notions of robbing or desecrating their graves.

- Unfortunately, this ploy did very little to deter foolhardy grave robbers who dared to risk any spiritual curse, for the sake of earthly gain.

- Of all the known tombs found in the Valley, only eighteen tombs are open to the public, although none of them are ever truly open at the exact same time.

- Because of past history of vandalism, and even attempts at stealing hieroglyph-panels, tourists who visit open tombs are now mandated to remain in file.